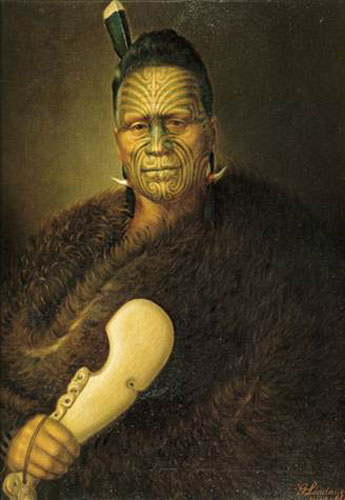

Tawhiao Tukaroto Matutaera Te Wherowhero

When Christian missionaries arrived he was baptised Matutaera (Methuselah) by the Anglican missionary Robert Burrows. It was not unusual for Maori of the time to adopt several names during their lifetimes to commemorate significant events and, in 1964, towards the end of the land wars, he was given the name by the Paimairire prophet Te Ua Haumene. The name translates loosely as binding the world. He was raised by his mother’s parents and his father, who had been a renown warrior leader encouraged him to be a man of peace. Supporters of the Maori King hoped that the position would help protect Maori land from Pakeha speculators and foster unity between tribes. Two major poblems which beset Maori in the years following the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840 were the appetite of the growing Pakeha population for more land, and disintegration of traditional Maori social structures as a result of European, and particularly missionary contact and influence. In a few short years Maori had gone from being total control of their affairs and destiny to being increasing influenced and dictated to by Pakeha. Tawhiao desperately tried to prevent his people from becoming embroiled in the Taranaki conflict and urged Governor George Grey to keep his Pakeha people to the lands they had acquired north of the Mangatawhiri Stream while Maori remained south of that boundary. He was however up against two very powerful forces. The first was the naturally warlike tradition of the Maori people and many his kinsmen, went without hesitation, to the assistance of their former enemies in Taranaki in the fight to keep Pakeha off their lands. They were in no doubt that their own lands would eventually come under a similar threat if the war was lost in Taranaki . The second powerful force was the hunger of Pakeha settlers for more land and the lengths they would go to get it. Tawhiao became Maori King during this dramatic and tragic time. He travelled over the huge area occupied by Tainui people and found them desperate need of assistance against the encroachment of Pakeha settlers. Had he been as warlike as his father, with the loyalty of thousands of fighting men and women from throughout the central North Island to call on, history may well have unfolded in a very different way but he was a true pacifist, as he had been taught, and totally renounced warfare between Maori and Pakeha. In one of famous proverbs he said, “Beware of being enticed to take up the sword. The result of war is that things become like decaying, old dried flax leaves. Let the person who raises war beware, for he must pay the price.” In the years after the Waikato War government officials met with Tawhiao several times to try settle their many differences but a true reconciliation was never reached. In 1878 the premier, George Grey, offered Tawhiao the return of unsold lands on the west of the Waipa and Waikato rivers, land at Ngaruawahia and financial aid for roads and other facilities. In return Grey wanted to open the King Country, closed to Pakeha after the wars, for a railway line running the length of the North Island. On his council's advice Tawhiao declined the offer. In July 1881, however, Tawhiao suggested a meeting with the government's representative at Pirongia where he ceremoniously laid down his weapons, saying, 'This is the end of warfare in this land.' It was not a surrender, as many have suggested, but a declaration that armed conflict would never be used to settle his many grievances. Three years later, in 1884, when he more than 60 years old Tawhiao Tawhiao led a deputation to England with a petition to Queen Victoria. He said simply that he was going to see the Queen of England, to have the Treaty of Waitangi honoured. The petition proposed a separate Maori parliament, the appointment of a special commissioner as intermediary between Pakeha and Maori parliaments, and an independent commission of inquiry into land confiscations. At a meeting with Lord Derby, the secretary of state for the colonies, Tawhiao acknowledged Queen Victoria's supremacy, and defined his own kingship as uniting the Maori as one people, not for purposes of separation but to claim the Queen's protection. However, subtle forces had been at work before Tawhiao’s arrival in Britain and Lord Derby referred the petition back to the New Zealand government. Premier Robert Stout replied to the Colonial Office by declining to discuss events preceding 1865, when the imperial government was responsible, and denying that there had been any infraction of the treaty since then. Tawhiao's specific proposals were dismissed or ignored. On his return to Waikato, Tawhiao sought solutions to Maori problems through the establishment of Maori institutions including institution of Poukai, where the King would pay annual visits to King movement marae to encourage people to return to their home marae at least once a year. The first Poukai was held at Whatiwhatihoe in March 1885. It was a day for the less fortunate to be fed and entertained. In 1886 Tawhiao asked the government that for a Maori council be established, with wide-ranging powers. This was rejected, and his references to rights under the Treaty of Waitangi ignored. However, in the late 1880s he created his own parliament, Te Kauhanganui, at Maungakawa, to which all tribes were invited and asked to participate. However, many tribes resisted any suggestion of Tawhiao's authority beyond his own people, and the Kotahitanga parliaments, which Tawhiao and Te Kauhanganui supported in some measure, presented another forum for discussion of Maori concerns and communication with the government. Tawhiao died on 26 August 1894 at Parawera and he was buried at Taupiri after a tangihanga in September which was attended by thousands. He did not live to see the fruition of his dreams for the return of Waikato land and the revival of self-sufficiency and morale among his people.. |

| < Back to Key Characters |

| Reproduced by kind permission of Tom O’Connor as published in the Waikato Times 13 July 2013 |

Tawhiao was the second Maori King who inherited the mantle from his famous father Potatau Te Wherowhero in 1860 just at the time of the outbreak of the First Taranaki War. He was of Ngati Mahuta, one of the senior iwi in the vast Tainui confederation of tribes. He was born at Orongokoekoea on the upper Mokau River towards the end of the musket wars between Nga Puhi and Waikato. He was originally named Tukaroto, which means to stand inside, to commemorate his father’s courageous stand in Matakitaki Pa when it was overrun by musket armed Nga Puhi in 1822.

Tawhiao was the second Maori King who inherited the mantle from his famous father Potatau Te Wherowhero in 1860 just at the time of the outbreak of the First Taranaki War. He was of Ngati Mahuta, one of the senior iwi in the vast Tainui confederation of tribes. He was born at Orongokoekoea on the upper Mokau River towards the end of the musket wars between Nga Puhi and Waikato. He was originally named Tukaroto, which means to stand inside, to commemorate his father’s courageous stand in Matakitaki Pa when it was overrun by musket armed Nga Puhi in 1822.