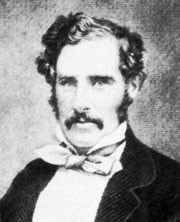

Sir George Grey

|

George Grey was born in Lisbon, Portugal, in April 1812 just eight days before his father, Lieutenant Colonel George Grey, had been killed during an attack by the Duke of Wellington's army on Napoleon's soldiers in the fortress of Badajoz, Spain. George Grey's mother, of English/Irish gentry stock , was Elizabeth Anne Vignoles of County Westmeath, Ireland. George was educated in England at a boarding school at Guildford, from which he ran away. After being tutored by the Reverend Richard Whately, George entered the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, in 1826. In 1830 he was commissioned ensign in the 83rd Foot Regiment, in which he served for six years in Ireland. He was promoted to lieutenant and awarded a special commendation for excellence after further studies at Sandhurst, but he disliked army serviceAlways thereafter he was opposed to great landed estates. He reached the conclusion that emigration was the solution to Ireland's ills and felt that new nations should be established, in lands of opportunity for the poor. When he was appointed to replace Sir Thomas Gore Browne as Governor of New Zealand in 1861, it was his second term in that position. He had been Governor from 1845 to 1853. During his first term Grey won the respect of those Maori he encountered. He encouraged tribal leaders to write down their accounts of Maori traditions, legends and customs. His principal informant, Te Rangikaheke, taught Grey to speak the Maori language and by the end of his term had learned a great deal about New Zealand and had a good knowledge of Maori tribal society. He was also a brave and determined leader and a skilful if unscrupulous tactician. During his first term he had quelled a rebellion by Hone Heke and Kawiti in the Bay of Islands and most importantly learned some of the intricacies of Maori mana and the power of tribal chieftainship. Following the fight between Te Rauparaha and British authorities in Marlborough in 1843 the settlers in Wellington and Nelson demanded retribution and relations between Maori and Pakeha became strained and difficult. Te Rauparaha was exonerated at Marlborough by Governor Fitzroy, who decided the Ngati Toarangatira leader had been acting in defence of his land and people. This created outrage among the European settlers and the colony was on the brink of open warfare. European settlers wanted rebellious Maori subdued and many Maori leaders had finally run out of patience with arrogant and dishonest Pakeha demanding more land. Grey was a different man when he was reappointed for his second term and was not above ignoring the law when it suited him. He was convinced that Te Rauparaha was the main influence over all the Maori living on both sides of Cook Strait and in July 1946 he had the old chief arrested and held without trial in Auckland for nearly two years. When Te Rauparha was returned to Porirua in 1848 most his tribe’s lands in the South Island, including the Wairau Plains, had been sold under duress in his absence and the old chief had lost much of his influence and mana and died less than a year later. When Grey arrived in New Zealand for his second term of office in 1861 the country was in again in a turmoil. The war over Waitara had ground to an unreliable truce under Major-General Sir Thomas Pratt but at a huge cost of almost a million pounds and the loss of many British soldiers and Maori fighters. Other tribes had refused to sell more land for European settlement as a result and were close to open war against the British. Grey decided the key influence this time was the King Movement in the Waikato and, using the same illegal tactics as he had used against Te Rauparaha, decided to take out the key to his problem, the Maori King and his supporters, and provoked a confrontation which would give him an excuse to use the army to destroy the organisation. He ordered a road to be built from Auckland directly towards Waikato knowing it would be seen and treated as a threat. This was the direct cause of the Waikato land War which spilled over into Taranaki again. Privately Grey expressed his hope that after several engagements the Maori would admit defeat, but this never happened. Although some tribes submitted, the war spread. Both Grey and his ministers wanted to confiscate land from the so-called rebel Maori and use it to place large numbers of military settlers in their midst but his ministers could not agree on how much land to take. Eventually they seized about three million acres. In the late 1860s the British Government decided to call all imperial troops home and force the colonies to accept responsibility for their own security. However the ongoing fights with Te Kooti, Titokowaru and other Maori generals created unrest among the settlers who were alarmed at the prospect of not having the British army to protect them. Grey stubbornly refused to finalise the return of the regiments, which had commenced in 1865 and 1866. In the end the British government had little alternative but to recall him in 1868. Grey returned to England, where he failed in an attempt to enter Parliament as a Gladstonian Liberal. He then returned to New Zealand, where he lived in his splendid home on Kawau Island, in the Hauraki Gulf. From there he emerged in 1874 to lead the fight against Julius Vogel's proposal to abolish the provincial governments set up under the 1852 Constitution. In 1875 Grey was elected superintendent of Auckland province and also to Parliament for Auckland City West. He fought vigorously in Parliament and in public to save the provinces, but without success. The Atkinson government persisted with abolition, but soon lost on a vote of no confidence over its lack of other policies. In October 1877 Grey became premier. His cabinet included some conservatives, as well as radicals such as John Ballance and Robert Stout. As he did not have a safe majority in the House, Grey asked for a dissolution, which was refused by the governor, Lord Normanby. Grey now stumped the country, stirring up considerable enthusiasm for radical causes, such as 'one man one vote'. However, in 1878 the country ran into a severe depression, which led to much unemployment. The next year the government lost a division in the House, and then failed to win a majority in the ensuing election. After the defection of four Auckland members, Grey resigned in October 1879. Although re-elected to the House of Representatives in 1893, Grey left for England in the following year and did not return. He resigned his seat in 1895. He and estranged his wife were reconciled in 1897, but both died in 1898, he on 19 September in a London hotel. He was buried in St Paul's Cathedral. |

| < Back to Key Characters |

| Reproduced by kind permission of Tom O’Connor as published in the Waikato Times 13 July 2013 |

Sir George Grey was a man of high intelligence but surprising moral contradictions. He was said to have been appalled by the poverty of the Irish people and shocked by the misery inflicted on them by the landlords but thought nothing of illegally dispossessing New Zealand Maori of millions of acres of tribal lands.

Sir George Grey was a man of high intelligence but surprising moral contradictions. He was said to have been appalled by the poverty of the Irish people and shocked by the misery inflicted on them by the landlords but thought nothing of illegally dispossessing New Zealand Maori of millions of acres of tribal lands.